|

The Salt Mines of Taoudeni are so far off of the beaten path that few maps agree on their precise location. Generally speaking, they are in northern Mali near the Algerian border, deep in the Sahara Desert of West Africa. Timbuktu, the nearest settlement of any substance, is 800 miles due south, that's how middle-of-nowhere it is. The area is home to the nomadic Tuareg, descendants of the Moors who for centuries brutally ruled over a vast desert empire. Nowadays, however, the Tuareg prefer the gentler arts and crafts of home decorating, and are typically as peaceful as mimes with blinders. Otherwise, the Mines are visited infrequently, sometimes deserted for months at a time. On this afternoon in late December, a solitary figure can be seen standing at the mines' main entrance, his features shrouded by the wildly raging simoom. The dust finally clears and ... why, it's Jean-Pierre Rampal, waving his flute in a jauntily salutatory manner!

Upon closer inspection, we discover that it's just salt--an outcropping from an aboveground salt dome with a vaguely humanoid shape. But someone has wrapped a pair of breeches around the lumpy bottom of the mineral block and embedded a two-foot length of chrome tailpipe into the top, and the result from a distance does bear a striking resemblance to the famous flutist.

Late flutist--both Rampal's heart and tongue stopped fluttering in the year 2000.

The sun-bleached block of salt also evokes a flutist because, when the wind blows across the mineral's numerous surface cavities, it produces a sound not unlike a piccolo with gastroenteritis.

It's making such a sound right now and, like the call of the mythical Siren, it draws dozens of desert denizens to it. Camels, acacias, land squid, Erwin Rommel, Jr.--each approaches the salt figure warily, subliminally aware that he has done so dozens of times during the last year, but with no recollection of the outcome. However, the sound is not only heard here in the middle of nowhere. On New York City's Upper East Side, in a certain art gallery of recent storied repute, a "Flute Players Through the Ages" exhibit featuring interactive animatronic figures of celebrated flutists past and present has just opened. Standing in the corner of the main gallery and reeking of potpourri, wearing a kilt and meticulously picking corn from his teeth is the expectorating image of James Galway. Seated next to him on an upended aquarium in which ancient coelacanths slowly swim upside down and backwards is Marcel Moyse. His mechanism appears to be malfunctioning because, as he bends down to re-tie his shoe, his left hand--the one holding his precious flute--instead repeatedly lashes out and thumps one of Red Grooms' subway golems, hard! In front of these two towers Jean-Pierre Rampal, all seven feet four inches of him, wearing only a smile and his Commandeur de l'Ordre National de Mérite medal strategically affixed to a codpiece that also houses a speaker from which emanates the sound of the piccolo with gastroenteritis. Like the alluring sound in the Sahara, it attracts the curious from all throughout the gallery. Most stop and gape first at Rampal, who holds his flute the way Borraka, the 14th century Moorish despot, held his enemies at bay--with centrifugal force. Those gallery-goers who survive the initial bout of vertigo often continue into the adjoining south wing, which features a female tap-dancing flute player installation. Her gyrations are as acrobatic as the adobe from which she is molded, and the noises that arise from her instrument are persuasive enough to soothe the savage yeast.

A young tatterdemalion has unwittingly stepped in front of the Grooms' subway rider just as the Moyse simulacrum is bending to tie his shoe. The flute hand suddenly shoots out and catches the lad squarely on his jaw, and he hits the floor like the ton of bric-a-brac that lines the gift shoppe walls. The tap-dancer in the south wing, meanwhile, has begun to disassemble her instrument in exquisitely ultra-slow motion. She pulls off the lip plate and places it on the floor in front of her. The keys, one at a time, follow, then the key cups, the tone hole rings, and the headjoint assemblies. All the while, she sustains a tattoo with her toes as agonizingly slow as the instrumental dissection. Eventually, all that remains is the flute tube. But instead of placing it alongside its fraternal components, where it seems desperately to want to go, she holds it firmly in her hand.

There is a commotion from the main gallery, and the ersatz Rampal comes striding through the doorway. Scowling, he lunges for the flute tube, but the tap dancer deftly shuffles out of the way, towards Buffalo. She tosses the tube up over her head, where it disappears with an alimentary groan through a seam that suddenly appears in the air a foot below the ceiling.

At the same time, 800 miles north of Timbuktu, a ferocious harmattan blows over the humanoid salt block and sends the tailpipe flying. Seeming to defy gravity, it soars up into the sky and vanishes into a stratocumulus. Only the land squid is around to hear what sounds like intestinal distress radiating from the cloud.

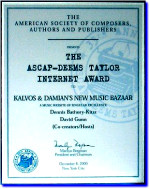

Order is restored to the Flute Players exhibit. The theme from Syrinx filters serenely through the gallery, Rampal is deactivated and dragged back to his welcoming perch and Moyse's left hand motion is reconfigured in American Sign Language. Order is also restored to this 447th episode of Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar, thanks in equal parts to the appearance of the blindered mime and to the recuperative powers of Kalvos.

|